Certain movements come naturally to us, like walking, running, sitting, and lifting. Yet, a lot of people complain about having pain in their backs and joints. It is estimated that globally, about 577 million people experience low back pain at a certain point in life (IASP, 2021), as a result of those completely natural, everyday movements. This is because if they are done improperly, the sheer number of times they are done during the day takes its toll.

There is a science to effectively using the body to avoid fatigue and injuries during everyday activities. The most important ones include lifting someone or something heavy, moving around in space, standing, sitting, or lying down (Lee, 2002; Karahan and Bayraktar, 2004). The rules of execution of these movements are called body mechanics. It refers to a coordinated effort from the muscular and neurological systems to maintain posture and balance properly engage the core during the motions of our daily living and sport activities.

Body mechanics in combat sports

Performing these seemingly simple movements with good coordination is especially important in high-impact activities like combative arts, as they involve direct confrontation and close physical proximity; a one-on-one conflict with an opponent often using partial or full body pressure. They present a huge risk of intense wear and tear on weight-bearing joints, which makes body mechanics a crucial aspect not only of carrying out techniques properly but also of reducing the risk of serious, and more often than not, recurring injuries.

Injuries very commonly create muscle asymmetry that results from the prolonged immobility of the injured body part (Brukner, 2012). This asymmetry can result in a snowball effect, leading to further injuries years after recovery, if the muscle balance is not regained with a well-planned physiotherapy program.

The need for refined body mechanics is a common demand in all fight sports, as impactful strikes use connected muscle groups together, not just the limbs. But it is most critical for those performing grappling arts and weightlifting, since these activities place high stress on the spine, the hips, and the knees while bearing weight, be it a free weight or an opponent’s body.

Body mechanics are a combination of posture, balance and motion, all of which influence how we coordinate a movement and how much stress we place on the body.

#1. Posture

The angles that various bodily components are held in while seated, standing, walking, lifting, lying down, or performing an action are referred to as posture. Posture can help the body’s organs work correctly and build muscle strength, both of which can reduce fatigue during exercise.

Posture is the foundation of effective body mechanics, proper power output, and avoiding injuries in fight sports.

Two types of postures can be differentiated: dynamic and static. When the body is virtually immobile, such as when it is standing, lying down, or sitting, we talk about a static posture. When someone is walking, lifting, or performing a movement, they are in a dynamic posture. Let’s look at the rules of proper execution for both groups.

Static postures

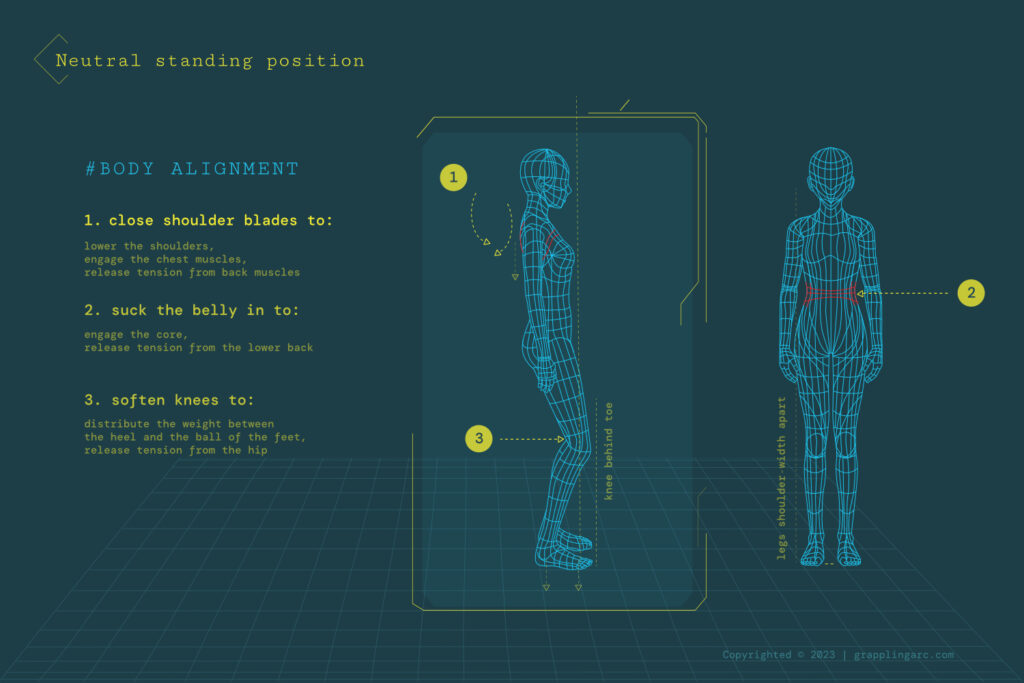

Standing position

In the neutral standing position, the spine should be in its loose “S” position with no excessive forward or backward curvature. The guidelines to achieve this state are the following:

- The head is balanced above the sacrum (end of the spine at the buttocks)

- The feet are shoulder-width apart

- The center of gravity passes through the ankle joints equally on both sides, so the body weight is distributed evenly between the two feet

- The joint centers of the pelvis, ankles, and knees are also equally spaced from the axis of gravity (Bond, 2007)

- The heels are pressed into the floor, and the balls of the feet push into the floor

- The knees are unlocked, which makes them feel slightly bent

- The shoulder blades are pushed together, so the shoulders are lowered and the chest muscles are engaged

- The belly is sucked in so that the transverse muscles (core) hold the torso in place, instead of relying on the back

The neutral standing alignment is what puts the least pressure on the joints, which means the soft tissue of the supporting system is under the least amount of stress (Karimi and Solomonidis, 2011). Neutral standing doesn’t need to be held all day, but the ability to set it up and instinctively align yourself before heavy lifting or striking is essential.

Achieving and getting back to this posture regularly during the day is the single most important component of body mechanics for combat sports. This synchronicity between the body parts enables the fighter to maintain stability, launch a strong attack, and navigate the fight efficiently. Without this, the fighter is unlikely to achieve the full potential of their body or get as far with their training as they wish to.

Our posture is the product of several years of adaptation to work and life circumstances. Same in case of incorrect postures, for example, collapsed shoulders commonly result from intense desktop work or emotionally demanding environments. The body adaptations that are part of this posture include shortened chest muscles, tight and stiff back muscles, and a forward-pushed head.

It requires months of targeted stretching to adjust the relevant muscle groups and correct a poor posture. The person won’t be able to stand straight and perform a steady stance without such corrective training. For competitive fighters, it is highly recommended to seek professional advice for a personalized program if their posture is suspected to be misaligned.

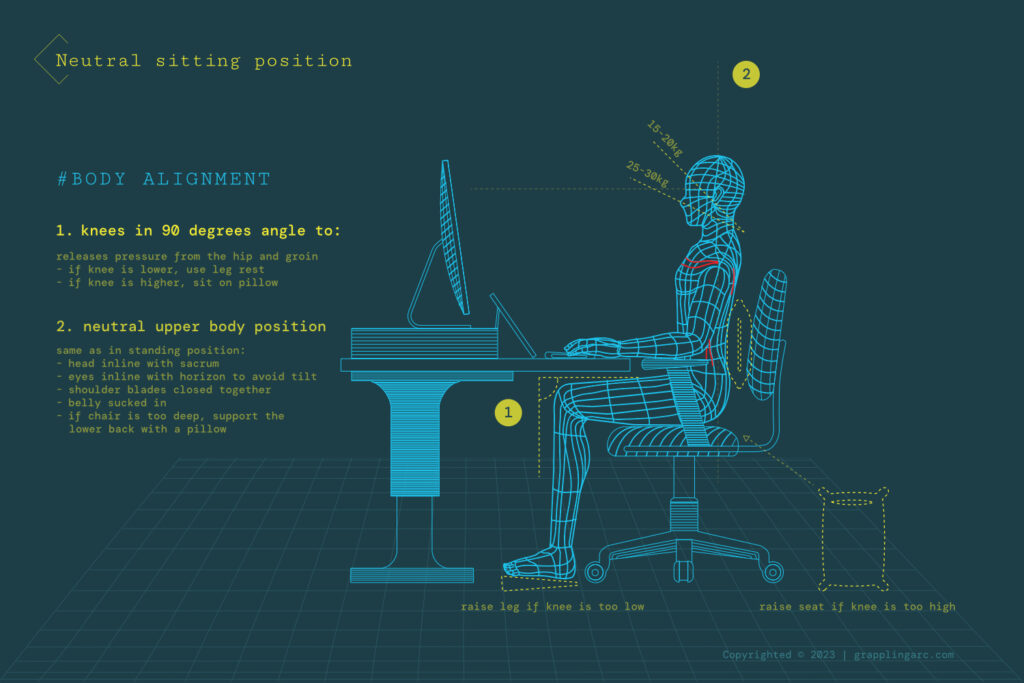

Sitting position

In sitting positions, it is also essential to keep our spines neutral and to minimize the pressure on the hips. In most cases, that requires the working environment to be adjusted to one’s particular body type, due to standard office furniture sizing being unfit for most people.

The rules that apply for proper sitting positions are quite significant in combat sports, because sitting puts tension on the groin, noticeably shortening the muscles over time and limiting leg movement. Those who do office jobs outside of the club need to do corrective exercises.

For those fighters whose daily job requires hours of sitting, it is strongly recommended to do regular groin and hip stretches during the day to keep the lower body flexible. Sitting numbs the legs due to immobility, while the edge of the seat often puts pressure on the nerves. Doing regular ankle and knee circles or stretches can also help to keep the legs mobile.

The following guidelines can help to keep the sitting position neutral:

- Keep the knees at 90 degrees to avoid stretching the hip muscles. Considering the one-size-fits-all furniture in most modern offices, you may need a leg rest beneath your legs (shorter people) or a pillow under your hips (taller people) to maintain this angle.

- For the upper body, keep the same posture as you would if you were standing, with the belly sucked in so that the transverse muscles take the pressure off the lumbar muscles, and with the shoulder blades closed so the shoulders are drawn back and the chest muscles work in collaboration with the back muscles.

- If the chair is too deep and there is space between your back and the back of the chair, it is advised to fill that space with a pillow to avoid C-curve resting and fatigue of the lower back.

- Keep the head in a straight position by aligning your monitor’s height to the horizon. In many cases, that would require adding a monitor or laptop stand. The more the head is tilted forward, the greater pressure it places on the neck. The usual laptop height tilts the head by around 30 degrees, which adds an estimated 15–20 kg of weight on the neck. When we look down at our phones, the angle can reach 60 degrees, which adds around 25–30 kg of pressure on the neck and can lead to acute headaches.

Sleeping position

Since on average, we spend one-third of our time asleep, it’s critical to understand how our bodies are arranged while we sleep. The objective is to keep our spines neutral, just as we do while we are conscious, to keep the pressure on the tissues and joints to a minimum. Here are some guidelines:

- Avoid sleeping on your belly or with your head propped up on a high pillow. These positions arch the back and can strain the spine. For anyone with back or neck pain, lying on your side or back is ideal for preserving a neutral spine.

- If you are sleeping on your side, place a pillow between your knees to neutralize the position of the pelvis and avoid tension on the hip muscles.

- If you are sleeping on your back, place a pillow behind your knees to maintain the proper alignment of your spine and lessen any potential stress placed on the lumbar area of the spine (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015).

#2. Balance

The capacity to control one’s steadiness when placing their center of gravity is known as balance. A hypothetical place where the weight of the body is uniformly distributed is called the center of gravity, referring to the fact that gravity pulls our body downward through this point toward the center of the Earth.

To maintain balance, a response is required whenever the axis of gravity deviates from the base of support (Slocum and James, 1968). Keeping one’s balance is basically the act of dynamically placing the center of gravity back over the base of support after being moved out of it. This applies to both dynamic and static postures.

All sections of our body can transfer their mass using joint movement, allowing a human body’s center of gravity to fluctuate based on what is required by any given motion. This is fundamental in the attack and defense strategies of combat sports. The place where the fighter’s mass is placed signals to the opponent whether they are in balance or off-balance, creating openings for strategic considerations.

Sport activities require us to maintain dynamic balance, the ability to maintain body posture and alignment while the body components are moving (O’Sullivan et al., 2019) and in some cases, actively under pressure. In addition, combat sports also require us to maintain that dynamic balance against an opponent or while bearing an opponent’s body weight, which involves resistance practice to gain proficiency.

Dynamic postures

#3. Motion

Motion is a concerted effort of joint movement in a three-dimensional space which creates a cohesive transfer of the whole body. The bones and muscles must operate in certain patterns for optimal results. The body is said to function via cycles of movements involving the torso, the head, the arms, and the legs. When executing a technique, you coordinate all of these components according to the movement framework of your chosen martial art. In grappling arts, where the body often ends up in unnatural positions, it is necessary to coordinate properly to save the joints form injury.

Posture during movement is highly dependent on the type of movement being executed, since the body parts move in relation to each other. For instance, in combat sports, the common stance is either a launch or a certain depth of squat, where the torso is moderately forward and one foot is placed slightly in front of the other to add more stability. When running, on the other hand, the torso is upright with the head aligned with the horizon.

The ideal posture for executing any given movement efficiently and safely is the first thing a fighter needs to learn during training. Mere observation of coaches is known to be less effective compared to being corrected by a trainer before or during the execution of the movement. This is partially because the learner can’t see their own posture from outside, and partially because they often need guidance on where they should distribute their weight.

Improving body mechanics requires non-resistance training, during which fighters have the opportunity to consciously follow their own movement in response to their opponent’s moves and observe the changes in their posture and balance. Pressure and speed are ideally added to the training once the mechanics are ingrained and performed correctly. It has been proven that training activities that gradually increase pressure produce the greatest outcomes.

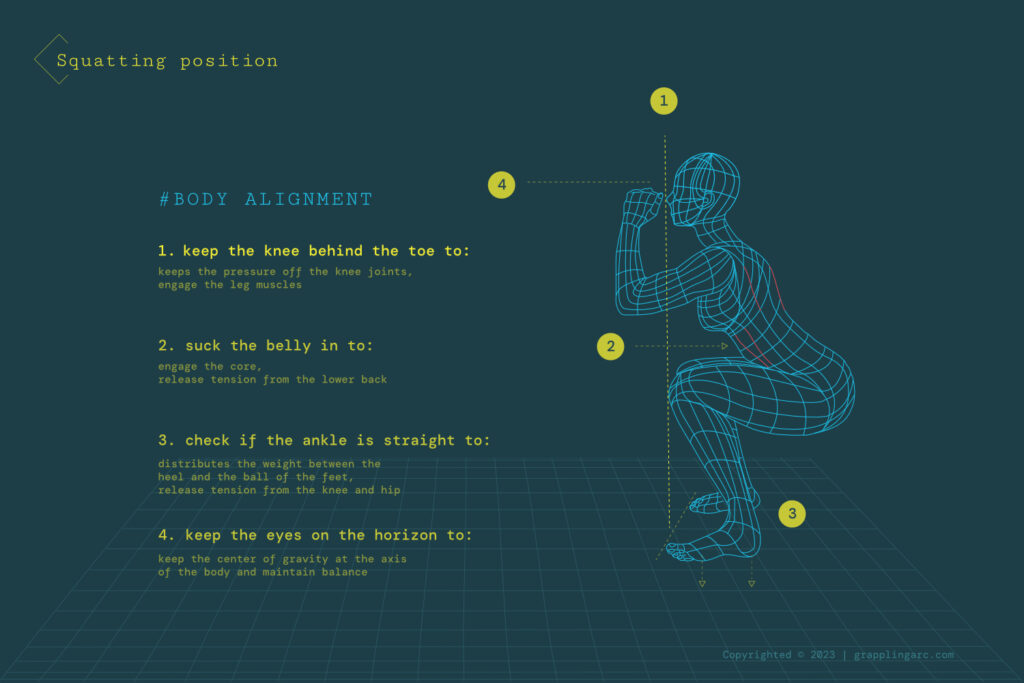

Lifting weight

When it comes to lifting weights, a proper combination of lifting techniques, muscle coordination, and posture is critical to achieving success without injury. The base stance for lifting usually involves feet spread wide apart while one foot is slightly in front of the other to keep balance. In addition, squatting and using the legs to rise back up rather than using the back to lift an object reduces the risk of injury to the spinal cord and hip joints.

Weightlifting studies between skilled lifters and beginners concluded that the ability to lift a larger mass is associated with a steady torso position and a smaller hip extension motion during the second knee bend transition (Kipp et al., 2012).

Guidelines for the squatting position:

- The knees need to be behind the toes regardless of the depth of the squat, otherwise the joints will bear the weight instead of the muscles.

- The upper body needs to follow the rules of the neutral standing position, with the belly sucked in, the shoulder blades drawn together, and the head aligned with the horizon to stay on the axis of the body.

- The ankles are straight to distribute the body weight equally between the two feet, the balls of the feet, and the heels. Avoid leaning inward toward the arch of the feet, otherwise the knees will collapse, putting pressure on the knee joints and ligaments.

Impact on performance

Studies have reported that successful athletes and those who display a high level of competitiveness in their practice have the best postural performance. High-level performers show excellence when it comes to maintaining balance. Even in dynamic conditions, such athletes tend to act quickly and efficiently to restore their balance and posture (Paillard, 2019).

The behaviors that define the use of our body are among the most ingrained in a person’s psyche and, as a result, altering posture and movement may be as challenging as giving up a bad habit. Even though everyone has been encouraged to “stand up straight” since they were little, children are exposed to bad posture at a young age by being forced to sit cross-legged on the floor and in one-size-fits-all seats at school (Wanless, 2017).

A person’s ability to move effectively is influenced by their anatomical structure, muscular capabilities, physical limitations, and psychological/cognitive capacity. When on a mission to improve one’s performance, the evaluation of the individual body features and postural components comes first, and the mental design follows. If needed, there are several strategies capable of improving motion efficiency.

One way of strategizing improvement is by using a targeted postural corrective training program, together with sport-related exercises. For runners, for example, postural training combined with Fartlek (alternating periods of faster and slower running) ensures that the athlete not only enhances muscle tone but also improves joint mobility and coordination, heightening their performance (D’Isanto et al., 2019). In combat sports, similar improvement can be reached by combining a postural corrective training program with specific drills.

One of the avenues that fighters can explore to improve their body mechanics and consequent performance is to look for sports physiotherapists. It is advisable to seek professionals who are well-trained movement experts and primarily work with fight sport athletes. One of the advantages of working with them is that they can examine the current status and identify gaps, tailoring specific body mechanics training to meet the unique needs of the fighter.

References

Barley, O. R., & Harms, C. A. (2021). Profiling combat sports athletes: competitive history and outcomes according to sports type and current level of competition. Sports medicine-open, 7(1), 1-12.

Brukner, P. (2012). Brukner & Khan’s clinical sports medicine. North Ryde: McGraw-Hill.

Knudson, D. V., & Knudson, D. V. (2007). Fundamentals of biomechanics (Vol. 183). New York: Springer.

Huston, R. L. (2008). Principles of biomechanics. CRC press.

Shultz, S. J., Houglum, P. A., & Perrin, D. H. (2015). Examination of musculoskeletal injuries. Human Kinetics.

Jensen, C. R., Schultz, G. W., & Bangerter, B. L. (1983). Applied kinesiology and biomechanics. McGraw-Hill College.

Bond, M. (2007). The New Rules of Posture: How to sit, stand and move. Rochester.

Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015; 1 (1): 40-43.

D’Isanto, T., Pisapia, F., & D’Elia, F. (2019). Running and posture. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise – 2019 – Spring Conferences of Sports Science. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2019.14.proc4.68

Human Kinetics. (n.d.). How applied sport mechanics can help you. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://us.humankinetics.com/blogs/excerpt/how-applied-sport-mechanics-can-help-you

International Association for the Study of Pain. (2021). The Global Burden of Low Back Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-global-burden-of-low-back-pain/

Kipp, K., Redden, J., Sabick, M. B., & Harris, C. (2012). Weightlifting Performance Is Related to Kinematic and Kinetic Patterns of the Hip and Knee Joints. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(7), 1838–1844. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e318239c1d2

Paillard, T. (2019). Relationship Between Sport Expertise and Postural Skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01428

Zhou, H., Yu, P., Thirupathi, A., & Liang, M. (2020). How to Improve the Standing Long Jump Performance? A Mininarrative Review. Applied Bionics and Biomechanics, 2020, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8829036